July 27, 2025

Written by: Theodora Mladenova

Nature-backed Finance

Nature-backed finance refers to an evolving field of financial innovation that recognises ecosystems like forests, wetlands, rivers, and grasslands as productive assets capable of generating measurable economic value. These ecosystems provide services such as water purification, flood regulation, biodiversity, soil fertility, and carbon sequestration. By monetising these services through credits, bonds, or stewardship agreements, financial capital can be directed toward ecological protection and restoration.

While carbon credits have traditionally dominated environmental finance, new mechanisms are expanding the toolkit: biodiversity credits, water credits, habitat banking, nature-linked bonds, and natural asset companies (NACs). These instruments are often described as part of nature-positive finance, but their outcomes depend heavily on governance. Without strong safeguards, they can also lead to extractive practices, the exclusion of local communities, or the privatisation of common resources.

Water Credits

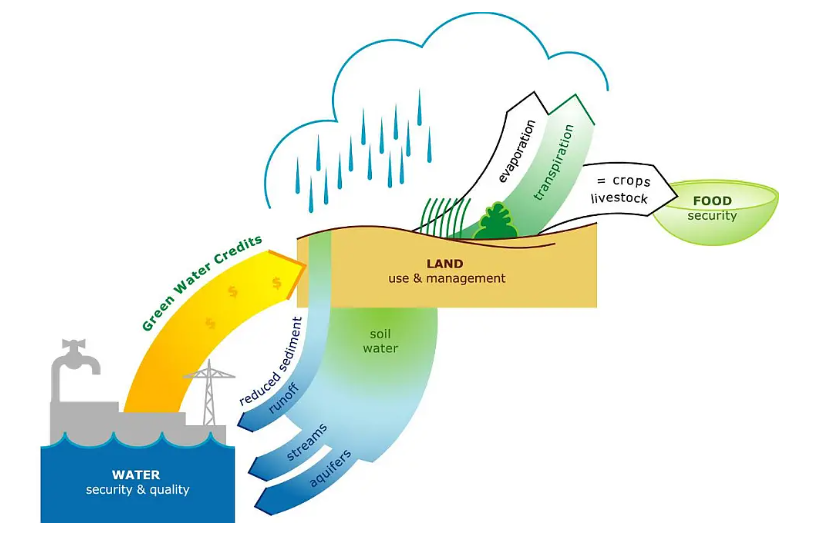

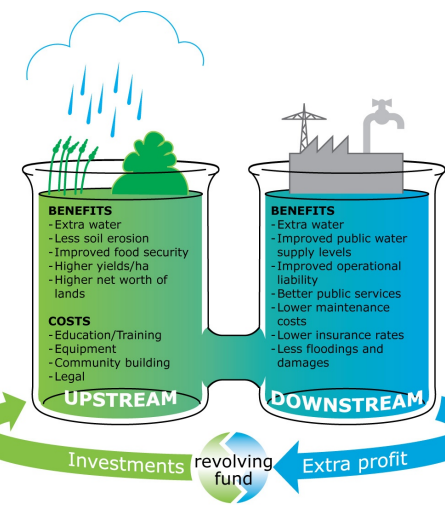

Water credits are a way to financially reward land stewards (typically farmers or forest owners) for managing their land in ways that improve water-related ecosystem services. These can include reduced erosion, increased infiltration, and improved water quality downstream. Originating in watershed pilots in Kenya, China, and Morocco, the model channels funds from downstream beneficiaries like cities or utilities to upstream stewards. In this model, water credits are often sold to utilities or cities that benefit from more stable, cleaner water supplies, creating a direct link between upstream conservation and downstream value.

Upper Tana Basin, Kenya

In Kenya’s Upper Tana River Basin, green water credits were piloted to reduce sedimentation in rivers that feed Nairobi’s drinking water. Farmers were incentivised to implement terracing, agroforestry, and other soil retention methods. As sediment loads dropped and water flows improved, utilities like Nairobi Water saw enhanced infrastructure resilience.

This pilot, supported by FutureWater and ISRIC, showed that even 20% adoption could generate downstream benefits valued between US $6 million and US $48 million annually, while costing under US $5 million. The program laid the groundwork for water-financing models that reward regenerative land use upstream.

Biodiversity Credits & Bonds

Biodiversity credits assign financial value to measurable improvements in species health, habitat quality, or extinction risk. Unlike carbon, biodiversity is highly local and complex, requiring metrics that are both scientifically rigorous and context-sensitive. Biodiversity bonds go further, linking investor returns to ecological performance, making nature protection an investable outcome.

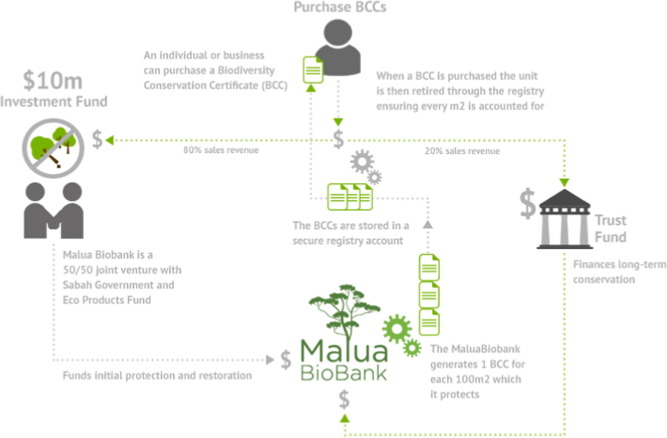

Malua BioBank, Malaysia

In Malaysian Borneo, the Malua BioBank set out to restore 34,000 hectares of rainforest bordering critical wildlife habitat. The initiative issued biodiversity certificates, each representing 100 m² of protected forest. Revenues supported patrols, restoration, and monitoring of endangered species such as orangutans and pygmy elephants.

Source: Andrea Brock, ‘‘Love for sale”: Biodiversity banking and the struggle to commodify

nature in Sabah, Malaysia

While ecologically impactful, investor interest proved shallow. With few market mechanisms to drive sustained demand, the project struggled to scale. The Malua case illustrates both the promise and pitfalls of commodifying biodiversity.

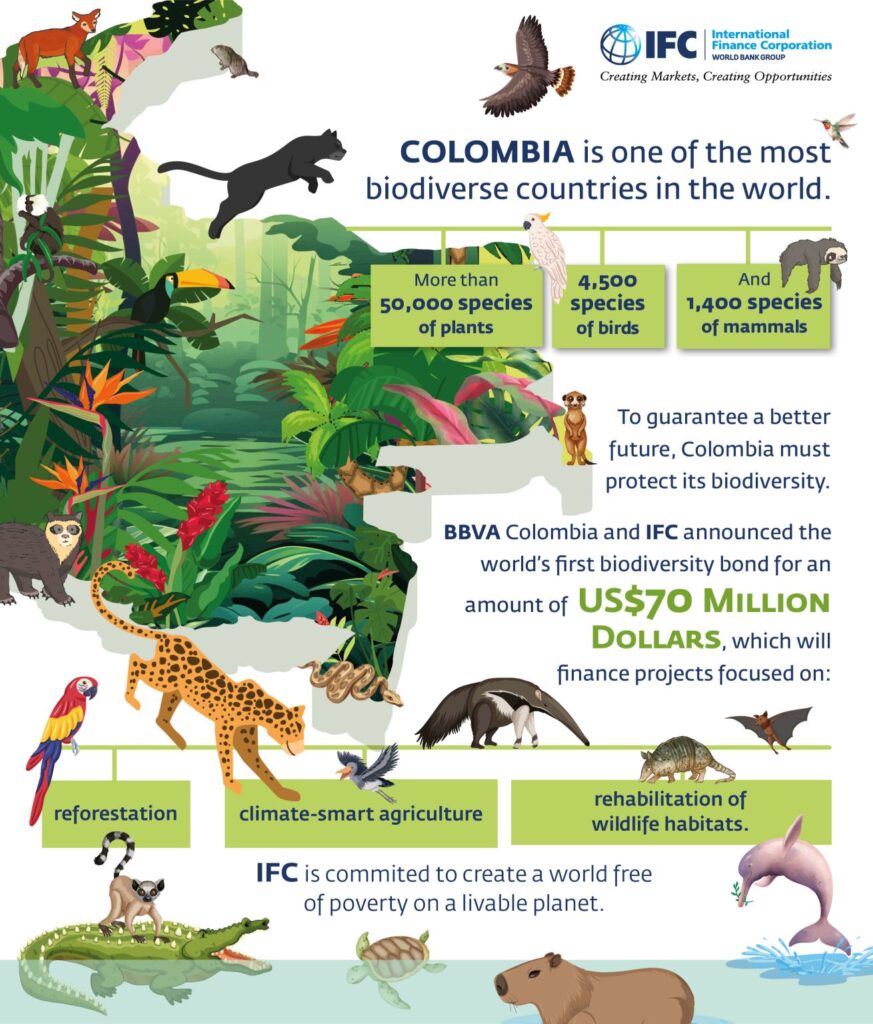

Colombia’s Biodiversity Bonds

At COP16, Colombia launched groundbreaking biodiversity bonds through Banco Davivienda and BBVA Colombia. Backed by IFC and IDB Invest, the bonds raised US $85 million to fund reforestation, agroecological transitions, and wetland restoration.

By embedding biodiversity criteria into mainstream bond structures, Colombia is setting a precedent for emerging-market biodiversity finance.

Source: IFC Financial Institutions

Habitat Banking & Mitigation Offsets

Habitat banking involves preserving or restoring ecosystems in one place to offset the destruction of similar ecosystems elsewhere. Developers buy credits from certified “banks” to compensate for unavoidable environmental damage. These systems are common in the U.S. and are expanding to other countries.

Uganda

Uganda is one of the first African countries to embed biodiversity offsets into national legislation. The 2019 National Environment Act requires developers to follow a mitigation hierarchy: avoid, minimise, restore, and offset; they’re also required to achieve no net loss of biodiversity.

Supported by the Wildlife Conservation Society’s COMBO+ initiative, Uganda introduced detailed national guidelines for biodiversity and social offsets. The Kalagala offset, for instance, protected over 20,000 hectares of riverine forest to compensate for habitat loss from dam construction.

East Devon Woodland Bond, UK

In Devon, the local council launched the Crystal Clear Clyst Bond – a community-issued financial instrument to convert farmland into biodiverse woodland. The project stacked carbon and biodiversity credits, which were sold to investors interested in both ecological returns and community impact. (more on stacking here)

The bond model provided a replicable framework for using local capital to fund nature restoration.

Hybrid & Blended Finance Models

Credit Stacking & Ecosystem Service Bundling

Nature-backed finance is evolving beyond single-credit approaches. Increasingly, projects are designed to stack or bundle multiple ecosystem services, allowing them to generate more than one type of environmental credit (such as carbon, water, and biodiversity credits) from the same intervention. This strategy expands potential revenue streams and appeals to a wider base of ESG-minded investors.

- Bundling: Multiple services sold as one aggregated credit (e.g. a wetland credit that covers water filtration + biodiversity habitat).

- Stacking (or layering): Separate, independently sold credits for each service derived from the same parcel.

For instance, a reforestation project that restores degraded land can sequester carbon (carbon credits), improve watershed function (water credits), and create wildlife corridors (biodiversity credits). When these services are measured and monetised together (credit stacking/ ecosystem service bundling), it creates a more financially viable and ecologically comprehensive investment.

Verra’s Multi-Benefit Certification Standards

Verra, a leading standards body in the voluntary carbon market, has been at the forefront of developing methodologies that enable projects to quantify and certify multiple ecosystem services.

Examples include:

- The Climate, Community & Biodiversity (CCB) Standards, which allow for co-certification of carbon credits with verified social and biodiversity outcomes.

- Work in progress to integrate water and biodiversity impact modules into core Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) projects.

- Methodologies under development for wetland and peatland restoration, where carbon, water regulation, and habitat benefits intersect.

These modular standards allow investors or buyers to support more holistic projects and better align with broader impact mandates.

Blended Finance Structures

In many of these hybrid models, blended finance plays a crucial role, using philanthropic, public, or concessional capital to de-risk private investment into nature-based solutions.

For example:

- The Upper Tana-Nairobi Water Fund used a combination of donor grants, utility payments, and investor capital to support upstream conservation.

- In Latin America and Africa, Project Finance for Permanence (PFP) has blended multilateral, private, and philanthropic capital to support Indigenous-led land stewardship at scale.

Blended finance structures help overcome high up-front costs, limited liquidity, and long investment horizons that often deter commercial investors from entering nature-backed markets.

Risks and Critiques of Commodified Nature

Nature-backed finance offers promise—but commodifying ecosystems also introduces real dangers. These include:

- Fungibility Issues: Unlike carbon (a globally fungible gas), biodiversity is site-specific, multidimensional, and relational. Attempting to standardise biodiversity credits across geographies risks diluting ecological meaning and masking net losses.

- Double Counting & Leakage: Ecosystem benefits may be claimed by multiple actors or transferred geographically in ways that allow for ecological harm elsewhere. For example, reforestation in one region cannot truly compensate for coral reef destruction elsewhere.

- Equity & Dispossession: Many nature-backed schemes fail to adequately involve Indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLCs), despite their role as de facto stewards of 80% of global biodiversity. Without Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC), these mechanisms risk reproducing colonial patterns of land alienation.

- Market Immaturity & Volatility: The global market for biodiversity credits is currently estimated at under $6 million—a tiny fraction compared to the carbon market. Without consistent demand, projects like Malua BioBank struggle to stay afloat.

- Perverse Incentives: Over-reliance on pricing mechanisms can encourage narrow optimisation (e.g., planting mono-cultures that yield high carbon but low biodiversity), undermining ecological complexity.

Using Nature as Collateral

An emerging trend in nature-based finance is to treat ecosystems as financial collateral, similar to real estate or mineral assets. Natural Asset Companies (NACs) and debt-for-nature swaps often involve pledging future ecosystem services in return for current investment or debt relief. While innovative, this model carries significant dangers:

- Illiquidity & Valuation Problems: Ecosystem services are hard to value with precision, especially over long periods. What happens when pledged biodiversity or hydrological services fail to materialise due to climate shocks, pests, or political instability?

- Risk of Default on Living Systems: If nature-backed loans are secured against a forest, for example, and that forest burns down or is degraded, who bears the loss? Defaulting on a forest isn’t like defaulting on a building.

- Financialization of the Commons: By allowing ecosystems to be traded, speculated on, or seized through foreclosure-like mechanisms, such instruments risk turning the global commons into private collateral. This threatens democratic control over shared resources.

- Loss of Sovereignty: In debt-for-nature swaps, low-income countries might cede long-term control over critical ecosystems to foreign bondholders or conservation trusts. This may create friction between ecological goals and national development priorities.

Malua Revisited

Despite its ambition, the Malua BioBank illustrates several of these concerns. The biodiversity certificates were ecologically sound but struggled to attract market demand, partly due to uncertainty in long-term biodiversity pricing and low liquidity. Moreover, the need to quantify ecological value in dollar terms created pressure to simplify nature into tradable units, undermining the richness of what was being protected.

Limits of Market Replicability

Even promising stewardship-based models can struggle with scalability. For example, some initiatives rely on patient capital from family offices or philanthropy, raising concerns about whether future biodiversity markets will serve elite investors more than local stewards.

→ See Qarlbo Biodiversity in Stewardship-Based Models

Pitfalls of Commodification

A striking example of how offset projects can masquerade as climate solutions while perpetuating harm comes from Mount Elgon National Park in Uganda. A carbon-offset initiative backed by a Dutch NGO and the Uganda Wildlife Authority promised to sequester 3.7 million tCO₂e, but only reforested 8,000 hectares, and up to 44% of new forest cover was encroached upon due to conflict. Villagers were forcibly relocated, and their removal was a condition of securing investment. Meanwhile, marketing materials continued to sustain a narrative of harmonious win‑win outcomes.

Bottom Line

Nature-backed finance walks a fine line: it can channel billions toward restoration, but it can also repackage nature into risky, alienating financial instruments. The challenge is to design financial tools that reflect ecological complexity and social justice, rather than reduce nature to a volatile asset class.

Stewardship-Based or Hybrid Models

Stewardship models focus on performance-based outcomes rather than commodification. They embed ecological science, local governance, and long-term care into financial structures. Some blend market mechanisms with public or philanthropic finance for durability.

Qarlbo Biodiversity (Louisiana)

Qarlbo, a Scandinavian family office, acquired 10,600 acres in Louisiana to test if biodiversity and forestry could co-exist profitably. By restoring native longleaf pine, protecting the endangered red-cockaded woodpecker, and practising mosaic harvesting, Qarlbo improved both ecological value and timber yield.

They made the first voluntary biodiversity credit sale in the U.S. and signed a biomass supply deal with Woodland Biofuels. Their integrated approach combines habitat health, sustainable yields, and market alignment.

Aurora Sustainable Lands / PFP (Canada and USA)

Aurora manages over 1.7 million acres of forest, shifting away from extractive models to long-term ecological management. Using Project Finance for Permanence (PFP), Aurora combines carbon markets, Indigenous-led governance, and biodiversity enhancement.

A landmark deal with Microsoft secured the purchase of 4.8 million carbon removal credits, enabling funding for restoration, selective logging, and community benefits across North American landscapes.

Rebalance Earth (UK and Global South)

Rebalance Earth treats nature (especially rivers, wetlands, and keystone species) as green infrastructure. By quantifying benefits like flood control, water purification, and carbon sequestration, they create financial structures where companies pay for resilience.

They recently launched a £150 million natural infrastructure fund with backing from the West Yorkshire Pension Fund, focusing on peatland and river restoration.

Rhino Impact Bond (South Africa)

This bond tied financial returns to the growth of black rhino populations in five conservation areas. Investors received payouts only if conservation targets were met, transferring performance risk to the private sector while aligning funding with outcomes.

The Rhino Impact Bond is a pioneering model of outcome-based conservation finance, but it also highlights key concerns. Conservation organisations have found it challenging to navigate the complexity of financial instruments, often ceding decision-making power to financial actors. The bond structure tends to favour charismatic, easily measurable species like rhinos, potentially narrowing conservation priorities and diverting resources from less visible but ecologically important species. Additionally, only sites with strong governance and monitoring infrastructure are likely to meet investor requirements, leading to unequal geographic investment. Crucially, the bond does little to shift long-standing power imbalances in conservation, with limited engagement of local communities and continued reliance on top-down approaches. These dynamics raise questions about whether financialised models can equitably and effectively support global biodiversity.

Considerations for the Road Ahead

- Use robust science: Biodiversity credits must rely on rigorous, verifiable metrics.

- Prioritize inclusion: Indigenous and local communities must be co-owners of benefit-sharing.

- Avoid commodification pitfalls: Recognise biodiversity’s relational and place-based nature.

- Blend capital types: Mix grants, public funds, private investment, and stewardship contracts.

- Support enabling policy: Countries like Costa Rica have demonstrated how public investment and legal recognition of ecosystem services—such as through their Payment for Environmental Services (PES) program—can drive national-scale restoration while respecting landholder rights.

Holding Complexity, Moving Forward

Nature-backed finance is expanding the boundaries of conservation funding. From water credits in Kenya to biodiversity bonds in Colombia and stewardship forestry in North America, it’s creating a more diverse ecosystem of financial tools. The challenge now is to design these tools with integrity—avoiding commodification traps and centring ecological and social resilience. Done well, nature-backed finance could become one of the 21st century’s most powerful engines for planetary regeneration.

Sources:

Green Water Credits – Upper Tana basin:

[1] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21513732.2014.890670

[2] https://www.futurewater.eu/projects/greenwatercredits/

[3] https://www.isric.org/projects/green-water-credits-pilot-kenya

[4] https://www.futurewater.nl/downloads/2009_Hunink_FW84.pdf

[5] https://edepot.wur.nl/172101

[6] https://www.futurewater.eu/projects/climate-change-upper-tana-kenya-en/

[8] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/40106594_Green_Water_Credits_Basin_identification

Malua BioBank Initiative:

[10] https://www.cbd.int/financial/offsets/malaysia-offsetmalua.pdf

[11] https://www.perc.org/2008/12/08/markets-for-biodiversity/

[12] https://www.cbd.int/financial/offsets/malaysia-offsetmaluapress.pdf

[13] Andrea Brock, ‘‘Love for sale”: Biodiversity banking and the struggle to commodify nature in Sabah, Malaysia https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281620270_”Love_for_sale_Biodiversity_banking_and_the_struggle_to_commodify_nature_in_Sabah_Malaysia/download?_tp=eyJjb250ZXh0Ijp7ImZpcnN0UGFnZSI6InB1YmxpY2F0aW9uIiwicGFnZSI6Il9kaXJlY3QifX0

[14] https://www.wrm.org.uy/bulletin-articles/banking-on-biodiversity-in-sabah-malaysia

[15] https://www.biodiversitycredits.se/some-examples-on-private-finance-for-biodiversity/

Colombia biodiversity bonds:

[17] https://www.ifc.org/en/stories/2025/financing-biodiversity-in-colombia

[18] https://www.ifc.org/en/pressroom/2024/28298

[21] https://www.ft.com/content/338dd196-8605-4d28-af8d-4faf5c8f7cb6

Habitat Banking & Mitigation Offsets:

[22] https://uganda.wcs.org/Initiatives/COMBO.aspx

[23] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00267-024-01982-6

[23] https://ecosystemsknowledge.net/resources/projects/crystal-clear-clyst-bond/

[24] https://hive.greenfinanceinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Crystal-Clear-Clyst-Bond-NEIRF-case-study.pdf

Hybrid & Blended Finance Models:

[25] https://www.forest-trends.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Stacking-Bundling-Resource-Paper-01-11-18.pdf

[26] https://www.fs.usda.gov/pnw/pubs/pnw_gtr842.pdf

[27] https://www.cbd.int/financial/pes/unitedkingdom-bestpractice.pdf

[28] https://nicholasinstitute.duke.edu/sites/default/files/publications/stacking-ecosystem-services-payments-paper.pdf

[29] https://www.forest-trends.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/doc_3308.pdf

[30] https://pdf.wri.org/factsheets/factsheet_stacking_payments_for_ecosystem_services.pdf

[31] https://www.policyinnovation.org/insights/beetles-in-a-pay-stack

Risks & Critiques:

[32] https://www.policyinnovation.org/insights/some-myths-and-misunderstandings-in-biodiversity-credit-markets

[33] https://www.lemonde.fr/en/environment/article/2024/10/30/at-cop-16-controversial-biodiversity-credits-are-under-discussion_6731040_114.html

[34] https://time.com/6234466/healthy-biodiversity-climate-change/

[35] https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rspb.2024.2353

[36] https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1365-2664.12398

[37] https://www.suerf.org/publications/suerf-policy-notes-and-briefs/debt-for-nature-swaps-a-two-fold-solution-for-environmental-and-debt-sustainability-in-developing-countries/

[38] https://medium.com/included-vc/biodiversity-credits-in-europe-will-it-work-3e4c9c3c20a7

[39] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S001671851400147X

Stewardship-Based or Hybrid Models:

[40] https://www.wsj.com/articles/qarlbo-biodiversity-aims-to-reshape-timber-production-64db21c7

[41] https://enduringearth.org/9-components-of-a-pfp/

[42] https://aurorasustainablelands.com/microsoft-ifm

[43] https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/land-use-biodiversity/how-carbon-finance-is-seeding-new-hope-northern-forests-2024-12-20/

[44] https://www.ft.com/content/45b30402-b598-4494-bd93-702416149e97

[45] https://www.wypf.org.uk/news/press-release-9-september-2024/

[46] https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2022/03/23/south-africa-pioneers-innovative-wildlife-conservation-bond-to-protect-black-rhinos-and-support-local-communities

[47] https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/03/31/investors-join-landmark-wildlife-conservation-bond-to-support-black-rhinos-and-local-communities-in-south-africa

[48] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/oryx/article/finance-and-biodiversity-conservation-insights-from-rhinoceros-conservation-and-the-first-wildlife-conservation-bond/2D5B8CBDB3B519920354F8226DC1A672

[49] https://www.iied.org/g04272

[50] https://www.fonafifo.go.cr/en/servicios/pago-de-servicios-ambientales/

[51] https://unfccc.int/climate-action/momentum-for-change/financing-for-climate-friendly-investment/payments-for-environmental-services-program