April 25, 2025

Written by: Theodora Mladenova

Outcomes Finance: A Results-Driven Funding Model

Outcomes finance is a dynamic and evolving field that links financial investments directly to the achievement of measurable social or environmental outcomes. It represents a shift from traditional input-based funding models to performance-based approaches, encouraging innovation, accountability, and long-term impact. This article explores the core tools and mechanisms of outcomes finance and their growing significance in addressing complex societal challenges.

Social Impact Bonds (SIBs)

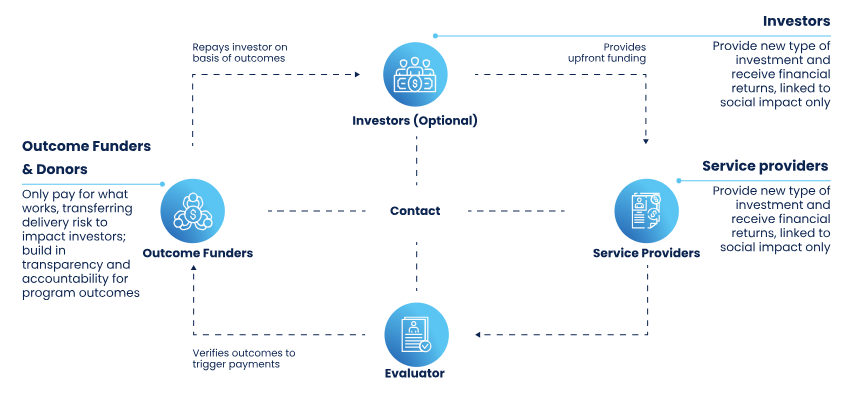

Social Impact Bonds, also known as Pay-for-Success contracts, are among the most well-known outcomes finance mechanisms. In a typical SIB, private investors provide upfront capital to fund a social program, which is delivered by a service provider. If the program achieves pre-agreed outcomes (such as reduced recidivism or improved educational attainment), the government or an outcome funder repays the investors with a return. If the outcomes are not met, the investors may lose their capital.

What makes SIBs innovative is their alignment of financial incentives with social progress. Repayments to investors are contingent upon achieving specific, measurable outcomes, rather than simply funding a service or activity. This structure ensures that all parties—investors, service providers, and governments—are focused on tangible results.

Moreover, SIBs effectively shift performance risk from the public sector to private investors. Instead of taxpayers bearing the cost of failed programs, it is investors who shoulder the financial risk, incentivising careful program design and rigorous implementation.

To maintain transparency and credibility, SIBs usually involve independent third-party evaluators. These evaluators assess whether the outcomes have been achieved according to agreed-upon metrics and methodologies, fostering trust among stakeholders and reinforcing the legitimacy of the results.

Despite their promise, SIBs are not without challenges. One of the most significant barriers is the high transaction cost associated with structuring and managing these complex deals. From legal arrangements to impact evaluations, the setup process is resource-intensive and often time-consuming.

Another hurdle lies in coordinating the many stakeholders involved—governments, investors, service providers, evaluators, and sometimes philanthropies. Aligning their diverse objectives and timelines requires skilled facilitation and strong relationship management.

Lastly, while SIBs emphasise measurable outcomes, capturing long-term impact remains difficult. Many social issues unfold over years or even decades, and current evaluation practices may not fully capture lasting change or unintended consequences.

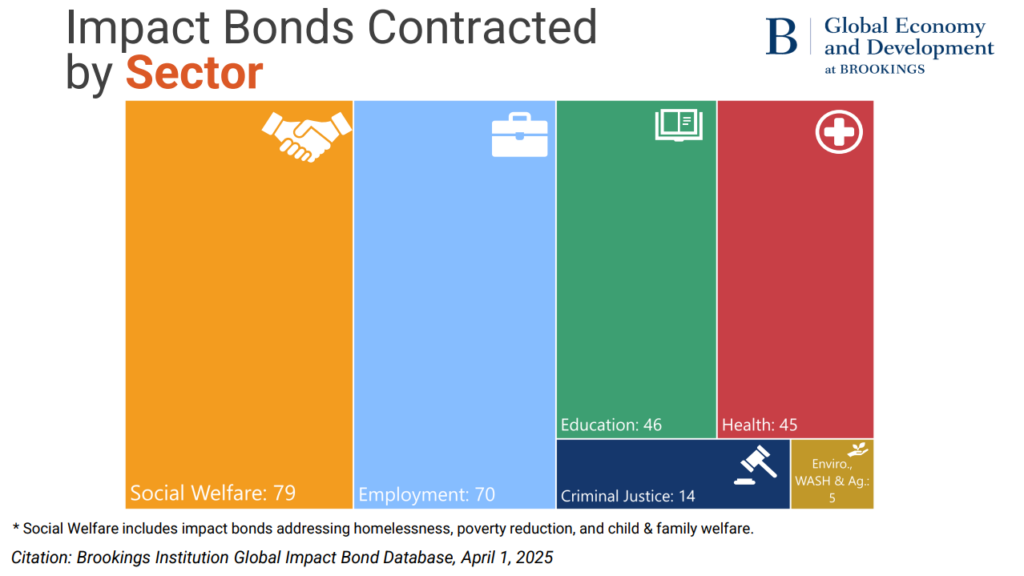

As of April 2025, there are 259 active impact bonds in 40 countries globally. Sectors covered include social welfare, employment, education, health, criminal justice, the environment and agriculture.

Case Study: YMCA of Quebec’s Alternative Suspension SIB

A compelling example of a Social Impact Bond in action is the YMCA of Quebec’s Alternative Suspension program. Launched in 1999, this initiative aims to reduce school dropout rates among at-risk youth aged 12 to 17 by providing structured support during school suspensions. Instead of staying at home, students participate in a three- to five-day program that includes academic support, individual counselling, and group workshops focused on developing social skills and self-esteem.

In 2021, the Government of Canada invested up to $4.5 million over five years to expand this program through a Social Impact Bond—the first of its kind in Canada focused on community safety. The SIB aimed to scale the program to 10 new sites across British Columbia, Ontario, and Quebec, reaching an additional 1,600 youth. Private investors provided the upfront capital, and the government committed to repaying them with interest only if predefined outcomes were achieved, such as improved student behaviour and reduced suspension rates. An independent third-party evaluator was engaged to assess the program’s effectiveness.

This innovative financing approach not only enabled the expansion of a proven program but also ensured accountability and measurable impact, demonstrating the potential of SIBs to address complex social challenges through collaborative investment.

Development Impact Bonds (DIBs)

Development Impact Bonds operate on the same foundational principles as SIBs but are tailored to the context of low- and middle-income countries. What sets DIBs apart is that the outcome payer is typically a third-party organisation—such as a philanthropic foundation, international development agency, or multilateral institution—rather than a government.

This structure enables high-impact interventions in regions where governments may lack the fiscal flexibility or administrative capacity to fund such programs upfront. Investors provide the initial capital, and service providers implement the programs. If outcomes—such as increased school enrolment, improved maternal health, or job placements—are achieved, the outcome funder repays the investors.

DIBs have been used in a variety of sectors, including early childhood education, public health, and employment. The model provides an opportunity to align incentives, foster innovation, and scale effective social programs in challenging contexts, while still placing a premium on accountability and measurable impact.

Despite their promise, DIBs also come with a distinct set of challenges. They often rely heavily on philanthropic capital, which may not always be predictable or sustainable. Coordinating multiple actors across international borders can introduce operational complexity and raise transaction costs. Furthermore, measuring outcomes across diverse geographies and cultural contexts poses significant evaluation challenges. These factors can make DIBs resource-intensive and difficult to scale without the right institutional support.

Case Study: Educate Girls DIB

The Educate Girls Development Impact Bond (DIB) is an excellent example of outcomes finance in action, particularly in the field of education. Launched in 2015, this DIB was designed to improve educational outcomes for girls in Rajasthan, India, by addressing the issue of out-of-school girls, a major challenge in the region.

The DIB focused on both enrolment and learning outcomes. It was structured to pay investors based on the achievement of specific, measurable results, such as enrolling out-of-school girls in school and ensuring that they gained key literacy and numeracy skills. The innovative model was the first of its kind in India and attracted attention for its ability to blend philanthropic, public, and private resources to tackle systemic issues in education.

In the Educate Girls DIB, private investors provided the upfront capital to fund the implementation of the program, which involved community mobilisation and targeted educational interventions. If the program achieved the agreed-upon outcomes, such as increased enrolment and improved learning outcomes, outcome funders (philanthropies or development agencies) would repay investors with interest. The pay-for-success structure ensured that investors only received returns if the program was successful in reaching its goals.

One of the key strengths of the Educate Girls DIB was its focus on rigorous monitoring and evaluation. Third-party evaluators were engaged to assess the outcomes and verify whether the targets were met. This transparency helped foster trust among all stakeholders, ensuring accountability and providing valuable data on the program’s effectiveness.

The outcomes were impressive: the program successfully enrolled more than 15,000 out-of-school girls, achieving a 92% enrolment rate, and learning outcomes improved significantly. The program also demonstrated how outcomes finance can drive large-scale improvements in education, even in challenging settings.

The Educate Girls DIB serves as a powerful example of how innovative financing can help scale social programs, achieve measurable impact, and provide a model for other development initiatives, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.

Outcomes-Based Contracts

Outcomes-Based Contracts are a broad category of financing mechanisms where payments are tied directly to the achievement of specific results, rather than the delivery of services or activities. Unlike SIBs or DIBs, OBCs may not always involve third-party investors—making them more straightforward but equally powerful tools for driving performance.

These contracts are particularly useful in public procurement or grant-making, where funders want to incentivise outcomes without the complexity of introducing private capital. They are widely used in employment services, homelessness prevention, and healthcare.

The key strength of OBCs lies in their adaptability. Because they can be structured to suit a wide range of projects and sectors, they enable funders to clearly define success and hold providers accountable. However, this same feature can introduce risk aversion – organisations may prioritise “easier” goals that are more likely to be achieved, potentially overlooking complex but important social needs.

Moreover, OBCs require robust data collection and performance measurement systems to track progress and determine payments. In contexts with limited capacity for monitoring and evaluation, these requirements can become a barrier to effective implementation.

Case Study: Australia’s Job Services Reform

Australia’s national employment services system underwent a major reform in the early 2000s, transitioning to an outcome-based contracting model that remains one of the most well-established examples of OBCs globally. Under this model, the government contracted with a network of private and nonprofit employment service providers, tying a significant portion of their payments directly to the achievement of employment outcomes.

Rather than paying providers for delivering training or counselling sessions, the system rewarded results—such as job placements and sustained employment over a set period (typically 13 and 26 weeks). This outcome-driven structure allowed providers the flexibility to innovate in how they supported job seekers, so long as they achieved measurable results.

Importantly, the Australian government built a robust performance management system to collect data, track outcomes, and facilitate continuous improvement. Providers were ranked on a star-rating system based on their outcomes, influencing future contracting and creating a competitive incentive for performance.

This model demonstrated how a government can drive accountability and improved service delivery without introducing third-party investors or complex financial structures. It also surfaced important lessons: while many providers improved efficiency and tailored their approaches, some also began “creaming and parking” – prioritising easier-to-serve clients and neglecting those with more complex barriers to employment. These challenges have shaped the evolution of the program and informed subsequent iterations.

Outcomes Funds

Outcomes Funds are a transformative evolution in outcomes finance. These pooled capital vehicles are designed to pay for results across multiple projects or service providers, reducing the transaction costs associated with structuring individual outcomes contracts.

The central idea is to create economies of scale. Rather than developing bespoke agreements for each intervention, Outcomes Funds standardise outcomes metrics, payment structures, and evaluation protocols. This approach helps streamline implementation and allows smaller or newer organisations to participate—broadening access and innovation.

However, managing Outcomes Funds comes with significant challenges. A robust governance structure is necessary to ensure that funds are allocated fairly, outcomes are achieved, and accountability is maintained across multiple programs. Coordinating diverse projects and stakeholders within a fund can create operational complexity, especially when dealing with varying levels of resources, capacities, and priorities. Additionally, while standardisation can help streamline processes, it must be done thoughtfully to avoid oversimplifying or diluting the impact of individual projects.

Case Study: The UK Life Chances Fund

One notable example of an Outcomes Fund is the UK Life Chances Fund, which aimed to improve the life chances of disadvantaged individuals across the UK. The fund pooled resources from the UK government and private sector partners to provide financing for multiple social programs. These programs focused on achieving specific outcomes, such as improving educational attainment, reducing homelessness, and increasing employment for disadvantaged groups. The standardised outcomes and metrics used in the Life Chances Fund allowed for scaling up successful interventions while reducing transaction costs, and it provided a framework for funding social programs that are evidence-based and focused on long-term impact.

Case Study: The Education Outcomes Fund (Middle East and North Africa)

The Education Outcomes Fund (EOF), an ambitious multi-stakeholder initiative backed by the Global Partnership for Education and the Education Commission, focuses on improving learning and access to quality education in low- and middle-income countries. EOF uses a pooled funding approach to support outcomes contracts in Africa and the Middle East, with payments tied to improved literacy, numeracy, and school attendance rates. One of its pilot programs in Sierra Leone, for instance, brought together NGOs, government entities, and private investors to deliver evidence-based interventions aimed at reducing the learning crisis. Early evaluations have shown promising results, reinforcing the potential of this model to drive systemic education reform.

By aggregating demand for outcomes and coordinating funding at scale, these funds help create a more vibrant and accessible market for impact-driven service delivery.

Blended Finance with Outcomes-Based Components

Blended finance involves strategically combining different forms of capital—typically public, philanthropic, and private—to mobilise resources for sustainable development. When these structures incorporate outcomes-based mechanisms, they add an additional layer of performance accountability.

For example, results-based grants may be disbursed only if certain health indicators improve. Impact-linked loans might offer reduced interest rates or principal forgiveness if specific social goals are met. Outcome-based guarantees can mitigate risk for private investors while ensuring that impact remains at the forefront.

This approach is especially powerful in sectors like renewable energy, health, and education, where financial returns alone may not attract sufficient private investment. By aligning capital flows with measurable impact, blended outcomes finance opens new pathways for scale and sustainability.

Case Study: Social Success Note for Safe Surgery in Africa

A standout example of blended finance with outcomes-based components is the Social Success Note (SSN) structure piloted by UBS Optimus Foundation and the NGO Smile Train in partnership with the Global Financing Facility. This model was used to fund life-changing cleft surgeries in countries like Tanzania and Ethiopia. Traditional donor funds were blended with private investment capital, and investors agreed to accept below-market returns in exchange for social impact.

In this model, Smile Train received upfront capital to deliver surgeries and post-operative care. Outcome payers—including foundations—only disbursed payments if predetermined metrics were met, such as successful surgeries and improved patient outcomes. If outcomes weren’t achieved, investors bore the risk, not the donors.

This structure demonstrated how innovative finance can unlock resources for critical but underfunded health interventions, ensuring accountability while scaling impact in low-resource settings. The SSN’s success suggests significant potential for applying similar models to other high-need areas in global health and development.

To realise their full potential, these models must be carefully structured to ensure that incentives are aligned, risks are distributed appropriately, and impact metrics are both meaningful and feasible to measure. Success depends on thoughtful design, transparent governance, and a shared commitment to learning and adaptation. These models thrive in ecosystems where public, private, and philanthropic actors work in concert, supported by robust evidence and mutual accountability.

Challenges and Considerations in Outcomes Finance

Despite its promise, outcomes finance is not without limitations. One of the most persistent challenges is the complexity of defining and measuring outcomes, particularly in social sectors where impacts can be diffuse or long-term. Effective measurement frameworks must balance rigour with feasibility and include both quantitative and qualitative indicators.

There are also concerns about equity. In a system where payments depend on hitting specific targets, there may be an unintentional incentive to focus on individuals or groups who are easier to serve, leaving behind those with more complex needs.

Furthermore, outcomes finance mechanisms often require significant upfront investment in legal structuring, stakeholder coordination, and evaluation systems. This can limit participation to well-resourced organisations, undermining inclusivity.

To navigate these hurdles, best practices are emerging. Co-designing programs with stakeholders—including communities served—helps ensure relevance and buy-in. Transparent methodologies and shared learning foster trust. And building the capacity of service providers strengthens the overall ecosystem.

The Impact Bond Dataset is a great first step to exploring real-life case studies of outcomes-based programs implemented around the World.

Charting the Path Forward

Outcomes finance represents a powerful paradigm shift in how we fund and evaluate social programs. By tying financial returns to real-world impact, these tools encourage efficiency, innovation, and collaboration. As the field matures, continued experimentation, learning, and adaptation will be key to unlocking its full potential. Whether through social impact bonds, outcomes funds, or blended finance structures, outcomes finance is poised to play a crucial role in achieving sustainable and equitable development worldwide.

Sources:

[1] https://socialfinance.org/what-is-pay-for-success/

[2] https://outcomesaccelerator.org/outcomes-based-finance/

[5] https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/the-basics/outcomesfunds/

[6] https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/understanding-social-impacts-bonds_7e48050d-en.html

[8] https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Impact-Bonds-Snapshot_April-2025.pdf

[9] https://www.russellwebster.com/roughsleepersib-final/

SIB YMCA case study:

[1] https://www.ymca.ca/news/ymca-alternative-suspension-program-grows-internationally

[2] https://thesvx.medium.com/ymcas-of-quebec-the-alternative-suspension-social-impact-bond-c5fe75f67acb

[3] https://inspiritfoundation.org/insights/government-canada-invests-program-youth-social-impact-bond/

DIBs:

[1] https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/investing-in-social-outcomes-development-impact-bonds.pdf

[2] https://dalberg.com/our-ideas/how-development-impact-bonds-work-and-when-use-them/

DIB case study:

[1] https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/knowledge-bank/case-studies/educate-girls/

[2] https://dalberg.com/our-ideas/lessons-educate-girls-development-impact-bond/

[3] https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/esg/development-impact-bond/

OBC:

[1] https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/the-basics/outcomes-based-contracting/

[2] https://obc.southerneducation.org/what-is-outcomes-based-contcontractingracontractingcting/

OBC case study:

[3] https://www.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-08/review-of-outcome-based-programs-june-2022.pdf

Outcomes Funds:

[1] https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/the-basics/outcomesfunds/

[2] https://www.gsgimpact.org/media/cajeziom/developing-outcome-funds.pdf

[3] https://www.socialfinance.org.uk/assets/documents/outcomes-fund-note.pdf

Life Chances Fund case study:

[2] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5e830040e90e0706ebaa81fb/LCF_FAQs_FINAL_DRAFT.pdf

[3] https://www.gov.uk/guidance/social-outcomes-partnerships

Education Outcomes Fund:

[1] https://www.educationoutcomesfund.org/

[4] https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/knowledge-bank/indigo/fund-directory/INDIGO-FUND-0019/

Blended Finance with Outcomes-Based Components:

Case Study: Social Success Note:

[2] https://andeglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Social-Success-Note-Playbook.pdf

[3] https://www.yunussb.com/articles/innovative-new-financing-solution-the-social-success-note

Challenges:

[1] https://www.cgap.org/blog/outcome-indicators-in-financial-inclusion-are-they-to-challenge

[4] https://www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doc/2024/inclusive-business-investing-guide.pdf

Other:

Impact bond dataset: https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/knowledge-bank/indigo/impact-bond-dataset-v2/