August 12, 2024

Written by: Theodora Mladenova

Doughnut Economics: A Framework for Sustainable Prosperity

Doughnut Economics, introduced by economist Kate Raworth in her 2017 book Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist, offers a paradigm shift from traditional economic models. Instead of prioritising endless growth, it emphasises thriving within the ecological and social boundaries of our planet.

The Doughnut Model Explained

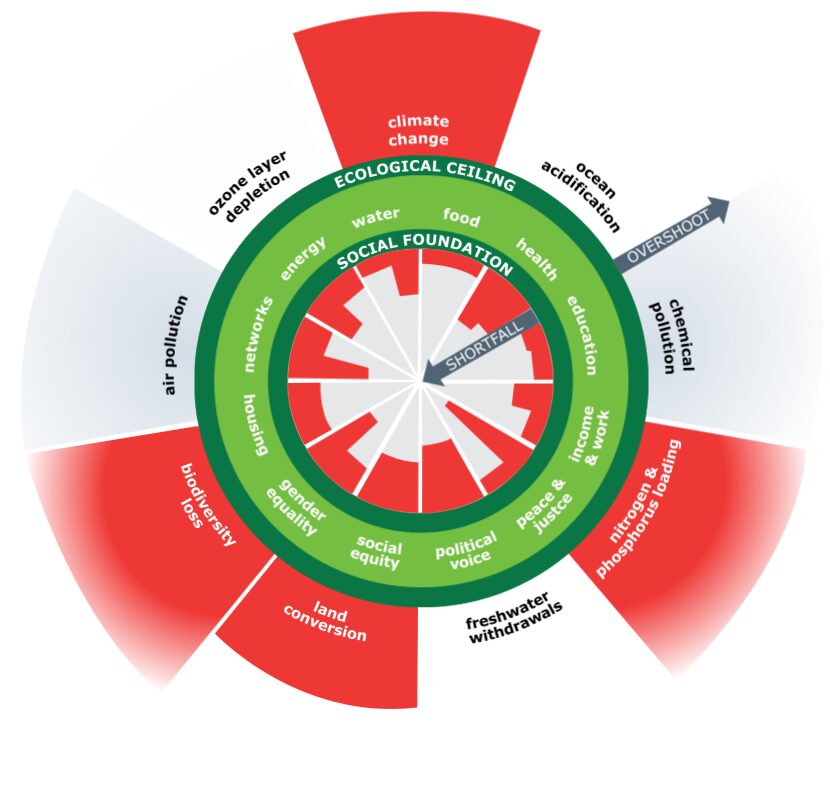

At the heart of this framework is the Doughnut, a visual representation of a safe and just space for humanity:

- Inner Ring (Social Foundation): Represents the minimum standards of living necessary for human well-being, such as access to food, water, healthcare, education, and housing.

- Outer Ring (Ecological Ceiling): Denotes the environmental limits we must not exceed, including climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution.

The space between these rings is where humanity can thrive without compromising the planet’s health.

Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist

Raworth proposes seven principles to guide economic thinking:

1. Change the Goal: Shift from GDP Growth to Thriving in the Doughnut

Traditional view: GDP (Gross Domestic Product) growth has long been treated as the primary indicator of a nation’s success.

Doughnut view: Instead of prioritising endless growth, the goal should be to ensure humanity thrives within the “safe and just space” of the Doughnut. That means:

- Meeting every person’s essential needs (social foundation)

- Without overshooting planetary boundaries (ecological ceiling)

Why it matters: Pursuing GDP growth often ignores inequality and environmental degradation. A thriving economy is one that enables well-being and sustainability, not just more output.

2. See the Big Picture: The Economy Is Embedded in Society and the Living World

Traditional view: Economics is often viewed in isolation, as if it operates independently from society or nature.

Doughnut view: The economy is embedded within society and the environment:

- It relies on natural inputs (resources, energy)

- It impacts communities, ecosystems, and future generations

Why it matters: Economic models that treat nature and society as “externalities” fail to account for real costs such as pollution, labour exploitation, or biodiversity loss.

3. Nurture Human Nature: Humans Are Social, Adaptive, and Contextual

Traditional view: Humans are rational, self-interested individuals (the “rational economic man”), always seeking to maximise utility*.

Doughnut view: Humans are interdependent beings, shaped by relationships, norms, emotions, and environments. We:

- Care for each other

- Cooperate and compete

- Respond to incentives and social cues

Why it matters: Good policy doesn’t rely on narrow models of selfishness; it encourages fairness, cooperation, and collective responsibility.

4. Get Savvy with Systems: Economies Are Complex and Adaptive

Traditional view: The economy is predictable and can be controlled with linear models (e.g. supply and demand curves).

Doughnut view: Economies are dynamic systems—they evolve, adapt, and often behave in nonlinear ways:

- Small changes can have large ripple effects

- Feedback loops and delays influence outcomes

- Tipping points can create instability or transformation

Why it matters: Systems thinking helps us design policies that anticipate unintended consequences and build resilience.

5. Design to Distribute: Equity by Design, Not by Redistribution Alone

Traditional view: Economic growth will eventually “trickle down” to everyone, and redistribution is a secondary fix.

Doughnut view: Distribution should be built into the design of the economy:

- Fair wages and labor rights

- Public access to essential services

- Inclusive ownership models (e.g. cooperatives, community land trusts)

- Tax systems that don’t favor wealth concentration

Why it matters: Inequality isn’t an accident—it’s often designed into institutions and systems. Changing the design can create more equitable outcomes.

6. Create to Regenerate: Align the Economy with Earth’s Cycles

Traditional view: The environment is a resource bank to extract from and a waste sink to dump into.

Doughnut view: The economy should regenerate ecosystems, not deplete them. This includes:

- Circular economies that eliminate waste

- Renewable energy systems

- Regenerative agriculture that restores soils

- Urban planning that enhances biodiversity

Why it matters: Degenerative economies undermine the very systems life depends on. A regenerative economy works with, not against, nature.

7. Be Agnostic About Growth: Prioritize Human and Ecological Thriving

Traditional view: Growth is good. More is always better.

Doughnut view: The economy should not be dependent on endless growth. Instead, ask:

- Does this serve human well-being?

- Is this sustainable within ecological boundaries?

Why it matters: In rich countries, further growth does not necessarily lead to better health, happiness, or equity. Thriving should replace growth as the benchmark of success.

Global Case Studies

Amsterdam, Netherlands

Amsterdam has adopted the Doughnut model to guide its post-COVID-19 recovery, focusing on sustainable development that balances human well-being and environmental health. The city has implemented projects such as imposing true-pricing in stores and promoting circular economy initiatives to reduce waste and resource consumption. This approach has influenced other cities like Copenhagen, Brussels, and Portland.

Melbourne, Australia

Melbourne’s “Regen Melbourne” initiative aims to transition the city into a regenerative and equitable urban environment. Key projects include the restoration of the Birrarung/Yarra River, aiming to make it swimmable by 2030, and the promotion of circular economy practices to reduce waste and resource consumption.

Leeds, United Kingdom

Leeds introduced Doughnut Economics through its “Climate Action Leeds” program, aiming to create a zero-carbon, nature-friendly, socially just city by 2030. The initiative focuses on community engagement, sustainable infrastructure, and equitable access to resources. Monthly events like “Imagine Leeds” bring together residents, businesses, and stakeholders to co-create solutions, fostering a collaborative approach to urban sustainability.

British Fashion Council, United Kingdom

The British Fashion Council (BFC) aims to make the UK a leader in circular economies through its Circular Fashion Ecosystems roadmap, part of its Institute for Positive Fashion (IPF). With the help of Amsterdam-based non-profit Circle Economy, the BFC plans to double circularity by 2032. Initiatives include workshops with industry stakeholders, knowledge sharing, scaling pilots, and collaborating with local governments to create necessary infrastructure. Starting in London and Leeds, the plan will adopt the Doughnut Economics model, focusing on balancing human needs with planetary limits.

Doughnut Economics offers a holistic approach to economic development, emphasising the importance of balancing human needs with environmental sustainability. By adopting this framework, cities and organisations can work towards creating a more equitable and sustainable future for all.

*Utility is a term used in economics and philosophy to describe the satisfaction, benefit, or value that a person derives from consuming a good or service, or from making a certain choice.

Sources:

[1] https://www.kateraworth.com/

[2] https://doughnuteconomics.org/

[3] https://time.com/5930093/amsterdam-doughnut-economics/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[4] https://doughnuteconomics.org/stories/regen-melbourne-an-evolving-journey

[5] https://www.climateactionleeds.org.uk/leedsdoughnut

[6] https://www.voguebusiness.com/sustainability/the-uk-has-a-plan-to-create-a-circular-fashion-ecosystem-bfc?utm_source=chatgpt.com